'Peace Girl' rises from hardship

Updated: October 15, 4:06 PM ET

'Peace Girl' rises from hardship

By Steve Marantz

ESPN.com

Soccer is the most international of games. Soccer brings people together. Both are reasons for 17-year-old Memuna Mansaray McShane to like it. There's still another: "I just play it 'cause it's fun."

Soccer is Memuna's game. To see Memuna command the

field, as she does for the varsity squad of St. Andrew's Episcopal School in

Potomac, Md., is to see a player determined and smart in the way of good

athletes everywhere.

"She plays the critical center back role for our team ... she's the eyes of the team," says Glenn Whitman, St. Andrew's coach. "She can see everything. And if she's not communicating, both constructively and loud, then we are losing an understanding of what we're confronting."

In many ways, on and off the field, Memuna is a teenage girl with normal abilities, concerns and interests. But at least one difference sets her apart. Below her right shoulder, where her arm should be, is a stump -- a reminder of her native land, the West African nation of Sierra Leone, and of how as a toddler, she was a symbol for hope and peace on an international stage.

It also is a reminder that, as she runs the field for St. Andrew's, her adolescent rite of passage is special.

Memuna was born amid a civil war that savaged Sierra Leone in the 1990s. Thousands of civilians were victims of murder, rape, mutilation and slavery, while children were drugged and forced to bear arms. Behind it, in a grab for Sierra Leone's "blood" diamonds, was Charles G. Taylor, president of bordering Liberia, whose weaponry and money fueled the rebels.

When Memuna was 2, rebel militia hunted down her family in a mosque where it had taken refuge. Her grandmother was shot dead as she cradled Memuna, and bullets shattered Memuna's arm. Her mother was shot as she ran to Memuna, and she died of her wounds within days. Memuna's older brother, who was 11, carried her to a hospital. By the time she received care it was too late to save her arm.

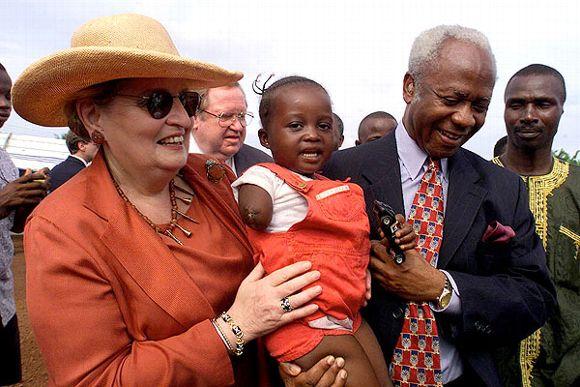

The story Memuna tells is that she was plucked from a refugee survivor camp on the orders of Sierra Leone's president, who was looking for a young amputee to help sway world opinion. He showcased her at peace talks -- an adorable, wide-eyed child with an amputated arm to dramatize the depravity of the strife. Memuna was 3 then and dubbed by foreign media as "peace girl," when she met U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who cradled her for a widely distributed photo.

"It allowed me to make very personal for an American audience what kind of suffering was going on in a country some people had never heard of," Albright told "E:60."

Images of Menuna and other victims eventually catalyzed international will to intervene and end the butchery in Sierra Leone.

Memuna was 4 when the Rotary Foundation brought her, along with seven other amputee victims, to the United States for treatment. She was 6 when Kelly and Kevin McShane adopted her. Kelly, who had served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Sierra Leone in the late 1980s, ran a nonprofit organization that served the poor and homeless; Kevin was a soccer coach at a private school. The McShanes lived in Washington, D.C., with their daughter, Molly, and son, Michael.

The McShanes opened their home and hearts to Memuna, with comfort and security. Almost immediately, Kevin introduced her to soccer at the recreational level.

"She was very successful at it at the very beginning because she's fast and she was, you know, strong and big and incredibly determined," Kevin recalled. "Because ... one of her fundamental things in life is to prove she's a normal kid."

Sports gave Memuna "confidence," said Kelly, and not only soccer. She tried rock climbing and swimming, and settled on basketball as a second sport.

She blended with her new family, made her grades, read the "Harry Potter" books and became an enthusiastic artist. She developed a big personality and appetite along with an endearing sense of humor. As she grew, however, Memuna became self-conscious about her stump, or "little arm," as she calls it. In a soccer match, a boy on the opposing team called her "one arm" and brought her to tears. Strangers asked her to explain how she lost her arm, which she loathed to do. She was fitted for a prosthetic but found it too uncomfortable and inconvenient to wear.

In 2008, the McShanes made a family trip to Sierra Leone. Memuna reconnected with her three older brothers (her father had died during the war), and was accorded celebrity status by residents. The trip helped her reconcile her roots, her parents said, but she continued to conceal her stump.

By the time she was a freshman at St. Andrew's, she invariably wore long sleeves. When she tried out for the soccer team her skill set was not an issue -- she was more than qualified.

"She had all the technical skills that we wish every one of our varsity athletes would have," said Whitman, her coach. "I was just more concerned of how protective she was of revealing the disability. I remember, distinctly, she would wear a Patagonia, a heavy fleece jacket, on some of the warmest days of preseason.

"My first worry was, 'She's gonna pass out. So let's keep her hydrated.' My second worry was, 'How are we ever gonna get past that discomfort, and her ability to open up to the girls?'"

It happened. As a freshman she spoke about her "little arm" to her advisory class, a tentative first step. Throughout her first two years at St. Andrew's, Memuna grew to trust her classmates, and especially her teammates. At the start of school in September, Memuna, now a junior, shed her long sleeves.

"I just want to stop wearing heavy sweaters -- I just want to stop hiding it," Memuna told "E:60." "These are my friends at school and I've been with them for three years, so I'm really comfortable with them."

Said Whitman: "She wears sleeveless shirts in front of the team. And to me, that is one of the most amazing growth mindsets and growth moments for not only Memuna, but for the rest of the team to have been part of."

Memuna pushed her transformation a step further -- she agreed to tell her story at school chapel before the student body and faculty. In mid-September she stood at a podium -- in a short-sleeved dress -- and delivered a poignant account of her travails. As she dabbed at her tears with tissue, she expressed gratitude and love for her adoptive parents and siblings. Before she finished she singled out two soccer teammates -- Kristin Butler and Caroline Graves -- who are out with injuries. Neither one, Memuna said, are "wallowing in self-pity". Both remain positive people "who have my back" and whose friendship she values.

Memuna concluded: "My message to you is that bad things will happen in your lifetime. But remember that something good always comes out of something bad. You may not believe me when it's happening to you ... but trust me on this one."

Little more than a week after Memuna's speech, an international court near The Hague upheld a 50-year prison sentence for Charles G. Taylor, the former president of Liberia, for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The next day, on a field in suburban Washington, D.C., Memuna played in a soccer match for St. Andrew's Episcopal. Her team won 9-0, and she scored a goal.

Taylor, the first head of state convicted by an international court since the Nuremberg trials after World War II, will spend the rest of his life behind bars. Memuna Mansaray McShane, a survivor of Taylor-backed atrocity, will finish her soccer season.

Steve Marantz is an "E:60" researcher and author of "Next Up at Fenway: A Story of High School, Hope and Lindos Suenos." Producer Matt Rissmiller contributed to this report.

For more on this story, watch "

For more on this story, watch "